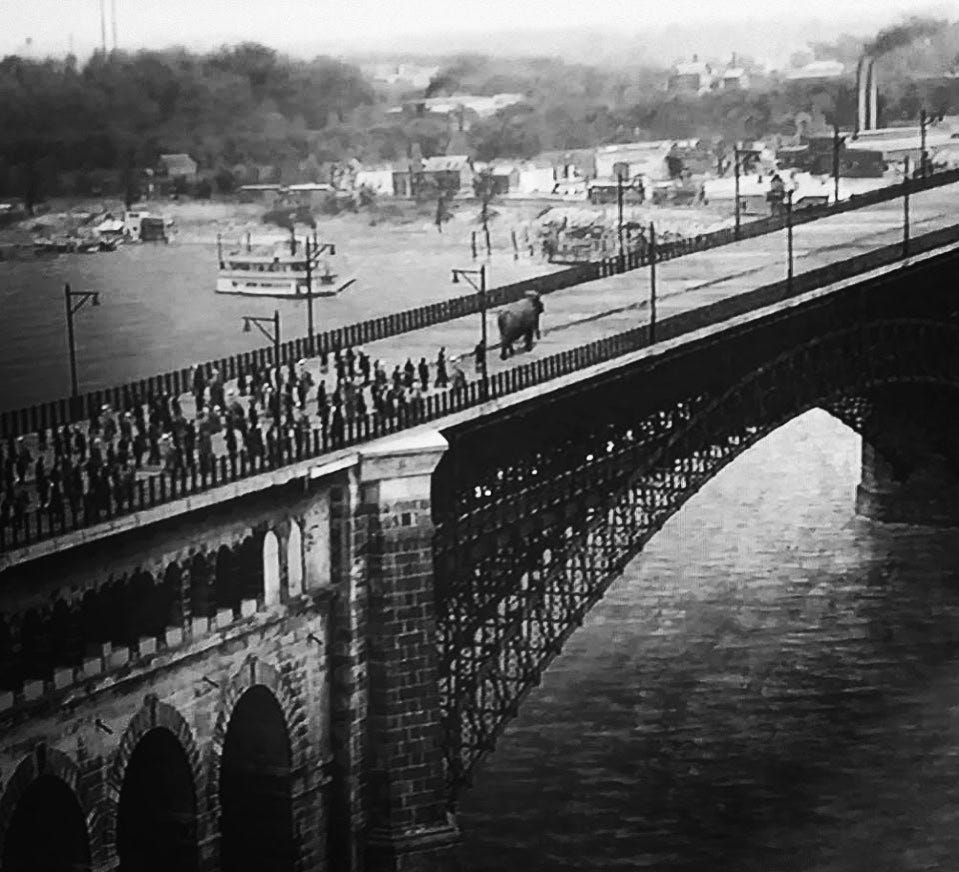

An elephant walk

On gaining trust for radical ideas

“Must we admit that, because a thing has never been done, it never can be, when our knowledge and judgment assures us it is entirely practical?”

- James Buchanan Eads

The Eads Bridge was one of the first major bridges to cross the Mississippi, and at the time of it’s completion in 1874, the longest arch bridge in the world. Owing to its construction, it is now the oldest bridge on the Mississippi as all the others that preceded it have collapsed over time.

Before it existed, crossing the river in the Saint Louis region was entirely reliant on steamboat services. Now, the everyday person could walk, ride their horse, or drive an early steam locomotive across the bridge.

The only problem?

Few people were brave enough to cross the bridge. The project was so unprecedented, the average person didn’t believe it was able to support the weight of the traffic that it would be anticipating. The fact it was designed by an engineer with no traditional accreditation did not help public opinion.

In a creative effort to prove the bridge was safe, an elephant was led across due to the popular superstition that elephants have a 6th sense for unstable ground. The animal was borrowed from a traveling circus and led across by John Robinson on June 14th, 1874. The elephant crossed from west to east without hesitation as crowds cheered the demonstration on from both sides of the river. A few weeks later, 300,000 people turned out for the Independence Day parade that coincided with the bridge’s opening day.

Longevity science would benefit from a similar display of audacity in order to validate to the public what insiders know: this is possible.

The most impactful thing the average person can do to extend their lifespan today would be changing how they exercise, eat and sleep for the better.

Despite this, the proof-of-concepts for radical longevity are out there. For many—including myself—cell reprogramming is the one with cause for most optimism.

Cell reprogramming is the process of taking a differentiated cell and tweaking it in such a way that it becomes a stem cell again. There are problems with this process we need to continue engineering solutions to—which I won’t go into here1—but I would still liken discovering the ability to reprogram cells to the discovery of splitting the atom. Once we saw that we could split the atom, it became obvious that we could engineer ways to continue exploiting this finding, making the process catalytic and developing the atom bomb. In the same vein, cell reprogramming has given us the mechanistic proof that we can rejuvenate a cell so as to make it biologically younger.

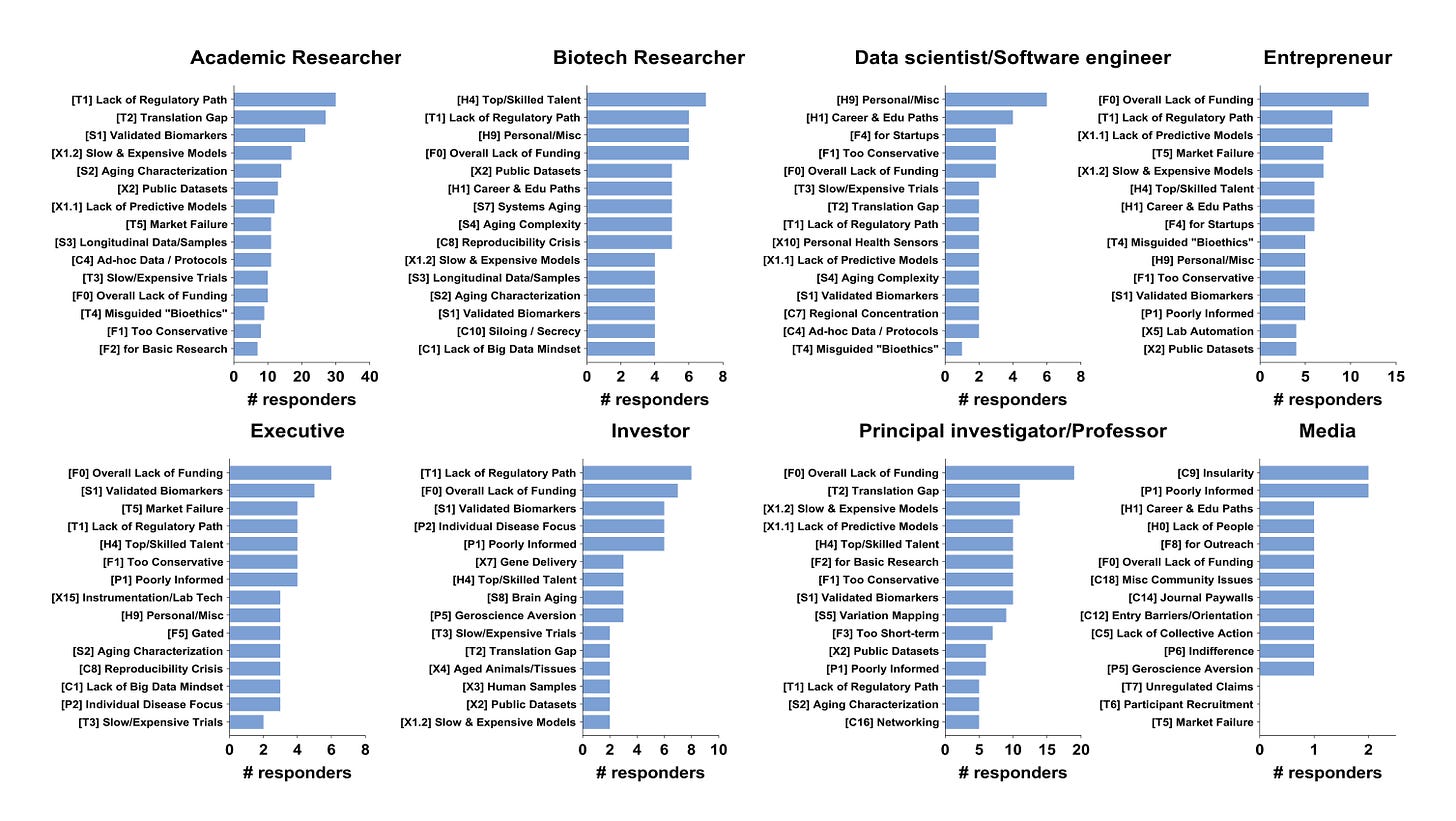

About a year ago, the Longevity Biotech Fellowship did a bottlenecks study polling 395 insiders for what the biggest holdups to progress in the space are.

The two results tied for top answer were a lack of validated aging biomarkers and an overall lack of funding. Neither of these answers struck me as particularly insightful or of encapsulating their underlying issues.

The more salient insights from this survey can be found in the breakdown of bottleneck answers by profession, as shown below.

In the case of validated aging biomarkers, it becomes clear that this answer is a recurring mean across all profession’s answers more so than any one’s top choice of bottleneck. As an answer, it represents a lack of consensus rather than the biggest impediment to progress in the field.

Moving on to funding, everyone always thinks they need more money until they get it and still don’t achieve what they thought they would. In this case, it serves as the null hypothesis for entrepreneurs, principal investigators, and executives alike in asking themselves: ‘What do I need to be successful?’

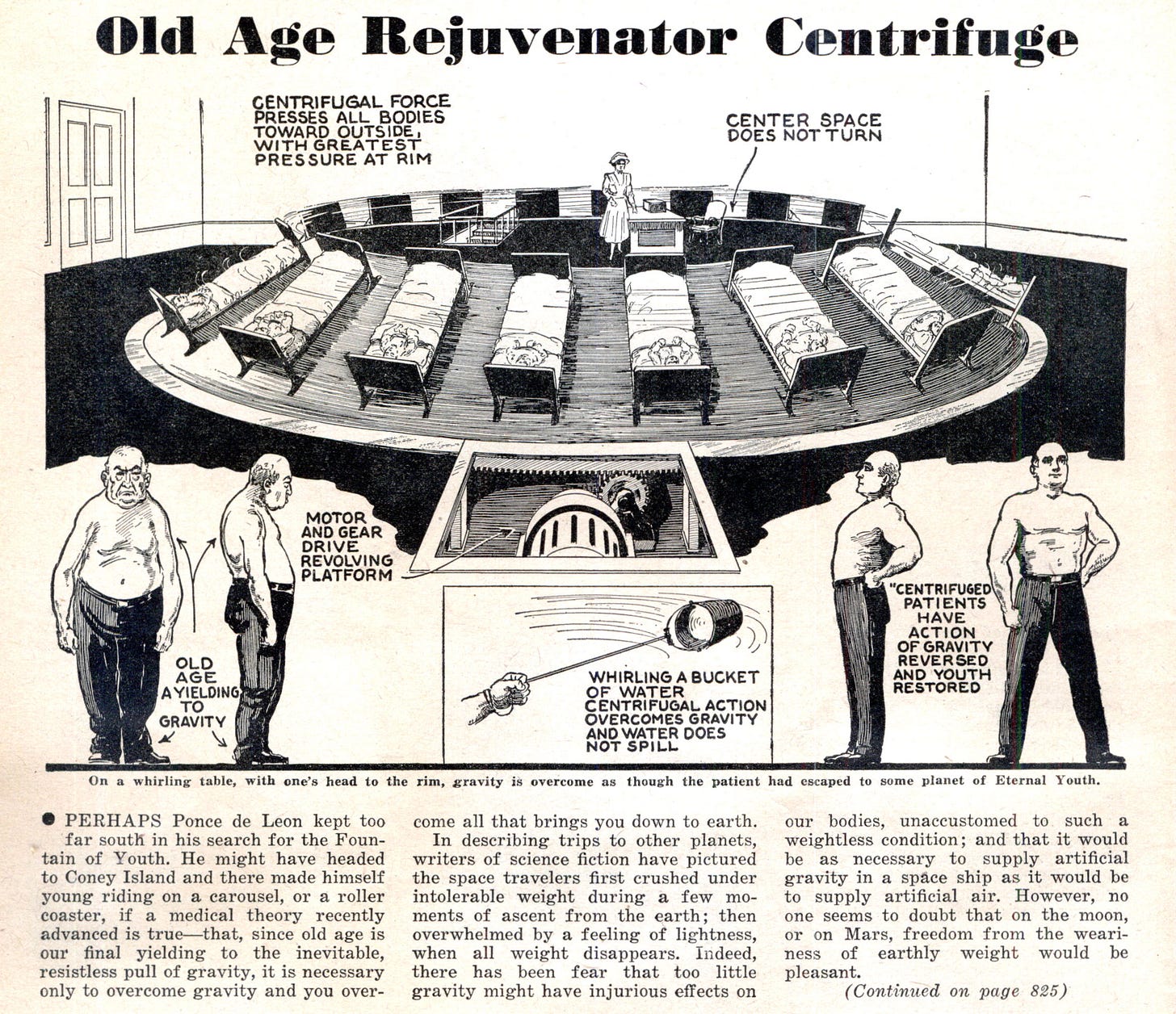

Most people who are in a position to invest in rejuvenation science do not think that it is possible—and rightfully so. The longevity space is ripe with misinformation propagated by enthusiasts on the periphery or at worst, insiders who justify creating undue interest in the hope it will pull more funding and attention into their work or the space as a whole. For over 100 years, this has drug down the ecosystem because it takes more energy to clean up bullshit than it does to create bullshit.

Despite what leaders in the field would go on Rogan and tell you, we are not just a year or two away from a drug that will extend everyone’s lifespans. There is much work to be done. As important as overcoming the technical challenges required to make rejuvenation science a reality, is reclaiming public trust in the endeavor.

Back to the bottlenecks study, the professions whose answers I was most interested in were from the first 3 categories shown on the above chart: Academic Researcher’s, Biotech Researcher’s and Data Scientist/Software Engineer’s.

Here we see the top answers from the people doing most of the work and they are still shared across the remaining professions: a lack of regulatory paths and top/skilled talent in the space.

The closest thing to an elephant walk moment I’ve seen of late directly addresses the problem of a lack of regulatory paths for aging drugs or therapies.

Loyal, a company developing longevity supplements for dogs, received approval from the FDA on the technical effectiveness portion of their conditional approval application for their first drug, LOY-001. This is the first time that the FDA has formally recognized that a drug can be developed and approved to extend lifespan.

Celine Halioua, the founder of Loyal, wrote in a blog post about how unprecedented this approval was:

As there was no established regulatory path for a lifespan extension drug, we had to design from scratch a scientifically strong and logistically feasible way to demonstrate efficacy of an aging drug. This process took more than four years, resulting in the 2,300+ page technical section now approved by the FDA. It included interventional studies of LOY-001 in an FDA-accepted model of canine aging and an observational (no-drug) study of 451 dogs.

For Loyal, creating the regulatory path for a lifespan drug has always been part of their plan.

Our product strategy has always been centered on earning FDA approval. While more challenging, time intensive, and expensive, I believe achieving FDA approval is critical to demonstrating the scientific legitimacy of lifespan extension drugs.

Most people know that the FDA has a rigorous system for ensuring that pharmaceutical products are safe and effective for humans. The same is true for veterinary medications — the drugs your vet prescribes to your dog, like the Rimadyl my senior Rottweiler takes for her arthritis, have been tested extensively and are regularly monitored by the FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine.

I’m bullish on what was achieved here because it aligns with what I mention above, that the upstream bottleneck in the longevity ecosystem is not funding as the study suggests, it is a lack of trust in the fact that what we’re working on here is possible. More trust will lead to more funding. It will also lead to more skilled talent, career paths for new entrants, and in addressing many of the other issues mentioned in the study.

It is a slow game to play. As Celine points out, it took Loyal 4 years just to reach this point. But maybe it does not have to be. That is the point of the elephant walk.

In Saint Louis where I’m based, I have to bite my tongue on longevity around the broader biotech ecosystem. The fact I’m unaccredited and the way I’m doing things already subtracts from my budget of weirdness points, so it would only create unnecessary skepticism in others’ minds to add to it I’m researching something most people find impossible.

This isn’t unique to our conservative midwestern culture. Despite the fact I am in favor of decentralizing innovation from the coasts, their openness for crazy and out of the box ideas is one of the biggest things these cities have going for them. It’s part of the culture to meet a stranger at a cafe, and not think twice when they tell you they’re building lightsabers or glow in the dark houseplants.

I’ve been doing a lot of moving around lately to learn wet lab techniques,2 and talk to scientists all over the world on a weekly basis. In doing this I’ve seen how others looking for answers to the same questions I am have to play this same game of obfuscating their core focus. Why?—To play to the public’s or their supervisor’s or their funder’s pallet for supporting work in this space.

It is a shame, because the obfuscation not only drains our energy but also our time. It’s led me to ponder the extent of silent complacency within our ranks—how many of us, constrained by our immediate circumstances, are subtly working towards grander ambitions yet find ourselves tethered to just a fragment of the issue at hand.

What we could achieve if we all walked together, I wonder.

Be in touch.

-Benjamin Anderson

Hello from NY where I am currently doing a 2 week stint with Ichor Life Sciences. By the time this is published I’ll be in Toronto to see a friend running YouthBio, a company focused on partial cell reprograming.

It’s remarkable how much resistance the academic community puts up to not doing it “their” way. Especially considering our current grant funding system is pretty recent in terms of the arc of science history. And, most (all?) of the seminal discoveries were way outside the lines of what other mainstream folks thought/considered incontrovertible truth. Extra weird given that the definition of science is arguably(?) pushing the limits of what we know, which has to include challenging current beliefs. Anyway kudos on what you’re doing!