Towards PID Control for Bioelectricity

Why membrane potential needs a volume knob

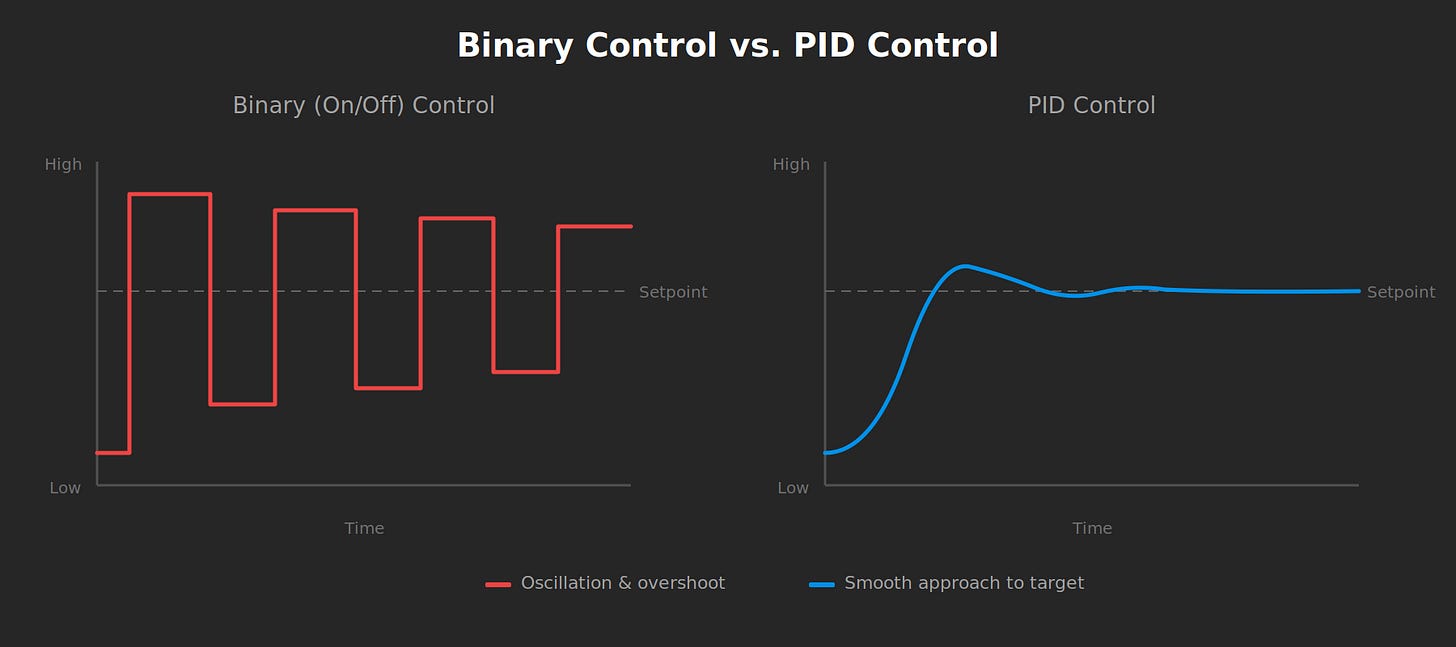

Before continuous feedback controllers, industrial temperature regulation was binary. Heat on. Heat off. The system oscillated around its target, wasting energy and producing inconsistent output. Chemical plants couldn’t hold precise reaction temperatures and HVAC systems cycled endlessly. Engineers understood thermodynamics fine but their control systems couldn’t speak in anything other than two words: more and stop.

PID control changed everything. Systems could finally approach a setpoint smoothly and hold it there. Entire industries emerged once control architecture matured from binary switching to variable tuning.

The field of bioelectricity is eagerly awaiting its PID moment.

We can depolarize cells and we can hyperpolarize them. By doing either, we shove membrane potential—hereafter referred to as Vmem—in one direction either towards a more positive or negative state and observe what happens. Results are remarkable enough that they have generated both excessive hype from some and reflexive dismissal by others… with both often making the same underlying mistake of treating bioelectricity as a standalone phenomenon rather than asking what it would take to actually control it.

Here are some of the things that we know.

In frog tadpoles, injecting human cancer genes causes tumor-like growths with all the classic features of cancer. When researchers force cells far from the tumor site into a hyperpolarized state, tumor formation drops by 30-40% even though the cancer-causing protein is still present in the tissue. What this shows is that despite the genetic instruction to form a tumor being present, the bioelectric state overrides it.

The proposed mechanism is that long-range signaling modulates HDAC1 activity and butyrate flux. More simply stated, voltage gradients are changing which genes get turned on or off, achieving epigenetic control of proliferation at a distance.1

This extends well beyond frogs.

Cancer cells tend to be depolarized. In aggressive breast cancers, forcing cells back toward hyperpolarization has been shown to trigger programmed cell death and slow tumor growth.23 Adult stem cells show similar patterns. Forcing depolarization keeps them immature even when they're being told to mature, while hyperpolarization reliably pushes them toward maturation. In rodent models, voltage-gated ion channels act as cancer triggers, with depolarization causing normal cells to behave like metastatic cancer cells.4

Put simply: depolarized cells like to divide and stay flexible, while hyperpolarized cells settle down and specialize.

Like most bioelectric work so far, these examples treat membrane potential as an on-off switch. Flip it one way, cells proliferate. Flip it the other way, they differentiate. This framing has produced impressive results but misses something fundamental.

Michael Levin is no doubt the modern champion of bioelectricity. Whenever I’m asked for an entry point into his ideas, I don’t share the planaria papers, Picasso frog or anthrobot stuff (although a few of these will get their spotlights below) - but rather a 2019 paper called: The Computational Boundary of a “Self”: Developmental Bioelectricity Drives Multicellularity and Scale-Free Cognition.

That is because it ties all his and others’ bioelectric output into the core upstream idea of this space, which is to treat cells as cognitive agents with goals where the bioelectric patterns encode target states.

The cellular collective uses Vmem as a coordinate system for navigating morphospace, which is the insiders’ term for a representation of the possible form, shape or structure of an organism.

Just last year, Levin published some simulation models that propose aging is an erosion of goal-directedness in multicellular systems where cells lose structural integrity primarily because they've forgotten what shape they're supposed to maintain, with accumulated damages we typically call the drivers of aging reframed as secondary factors.5 Rejuvenation in these models comes from injecting differential patterns, analogous to bioelectric gradients, that reactivate dormant memories of original anatomy.

This suggests Vmem functions less like a light switch and more like a GPS coordinate where you can specify a destination and let cells navigate there themselves. If pathology stems from losing that destination then the implied therapeutic strategy shifts from fixing broken parts to re-specifying targets. This said, GPS coordinates require precision. A binary signal won't do.

Evidence continues to mount that the pattern of change in membrane potential over time carries information beyond the voltage snapshot.

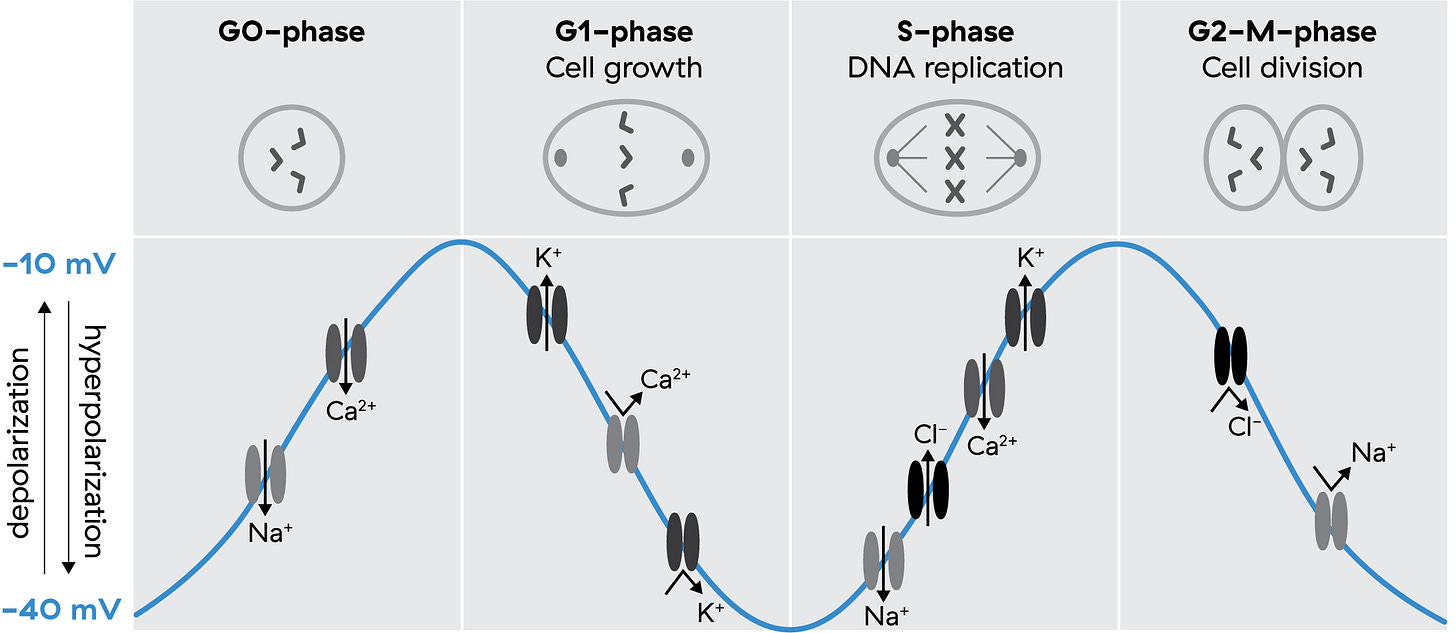

Since the 70s, we’ve known that Vmem undergoes rhythmic fluctuations during the cell cycle.6 Depolarization marks the transition from dormancy (G0/G1), intermediate hyperpolarization accompanies the start of DNA replication (G1/S), and deeper hyperpolarization precedes division (G2/M).7 This sequence directly regulates proliferation via ion fluxes and cyclin-dependent kinases showing again that it isn’t a single voltage but a trajectory of Vmem states that gates progression through the cycle.

More recent work from Levin and colleagues shows that oscillatory bioelectric states couple to transcriptional oscillations. In other words, rhythmic voltage changes synchronize with rhythmic gene activity, enabling a kind of spatio-temporal coding where cells oscillate between depolarized and polarized states, and these patterns encode distinct outcomes.8

In one example from embryogenesis, temporal shifts in voltage patterns prepattern gene expression for craniofacial structures. When researchers experimentally altered the voltage pattern, the resulting face morphology changed accordingly demonstrating that dynamic voltage sequences can override what genetics alone would specify.9

Most directly, voltage-gated ion channels have memory.10 Channel activity differs depending on whether membrane potential is rising or falling toward the same value, even if it lands at the same place. The same average Vmem yields different ion fluxes and downstream signaling depending on how it got there.11

All this to say, the cell’s response depends on trajectory and how it arrived at a given state. Static interventions like ‘hyperpolarize and hold’ leave information on the table. The language includes vocabulary, sure, but also syntax. Sequences, rates of change and oscillatory patterns all carry meaning.

We’ve been shouting single words when, like us, the biology speaks in phrases.

By this point you might be asking:

How do we know bioelectricity is the best way to communicate with cells?

Cells sense chemical, mechanical, and electrical stimuli among others. Each could theoretically serve as an intervention point.12

Chemical signaling faces a combinatorial explosion with near-infinite small molecules at varying concentrations, without a path to reliable real-time measurement of downstream effects. The search space is vast, and feedback is slow.

Mechanical signals propagate slowly and are limited by the physical properties of tissue. They're highly local and force applied to one region doesn't easily coordinate behavior across distant cells. Effects depend heavily on the various contexts of tissue stiffness, cell density and extracellular matrix composition among other things. Lastly and most convincingly to me, mechanical inputs largely exert their influence by modulating ion channel activity at the membrane, converging downstream on electrical state anyway.

Electrical signaling satisfies the constraints that matter.

Speed: ion flux occurs on timescales orders of magnitude faster than diffusion-limited chemistry or mechanically-propagated forces.

Shareability: gap junctions allow voltage changes to propagate across large cell populations as a coherent signal.

Tight coupling: membrane potential directly gates channels controlling gene expression, cytoskeletal dynamics, and metabolic state.

There’s an asymmetry in causal weight here. While there are many examples of transient Vmem modulation producing permanent morphological reconfiguration, the same cannot be said for a mechanical or chemical intervention that doesn't implicate Vmem anyways.13

In planaria, brief depolarization resets anterior-posterior polarity, yielding two-headed worms with stable anatomical changes propagated across generations. No ongoing input is required here. A friend and colleague reproduced the experiment himself in his basement, you can read his post on that here. Yes, a chemical is what is used in order to produce the depolarization, however the specific chemical that is used doesn’t matter so long as it is targeting the important causal lever, which is the membrane potential.

In frogs, researchers triggered eye formation in tissue that wouldn't normally become eyes by using optogenetics to shift membrane voltage in that region. The tissue's physical structure stored what voltage instructed but mechanical interventions alone can't achieve the same reset unless they happen to engage bioelectric pathways upstream.

These examples show the capacity for Vmem to function as an instruction set for what to build as opposed to a record of what happened.

The tools we have available now don’t match the opportunity to write to the body using this instruction set.

Pharmacological agents modulate Vmem via channel blockers, openers, or pump inhibitors. Optogenetics uses light-activated channels in genetically modified cells. Genetic engineering over-expresses or knocks down specific channels and pumps. All of these are blunt. They lack cell-type specificity, cause off-target effects, and can’t achieve the spatial and temporal precision that human translation requires.

Optogenetics comes closest to temporal control, but it requires genetic modification, which puts a strict limit on clinical translation, and light penetrates poorly into deeper tissue in the body. Pharmacology can reach those depths but lacks precision in both space and time.

None of these methods can execute “hyperpolarize for two hours, then partial depolarization, then gradual return to baseline.” They can flip switches, but they can't turn dials.

What's missing is volume knob control that gives us continuous, reversible and spatiotemporally precise modulation of Vmem dynamics. We should be seeking the biological equivalent of PID control, where feedback-driven adjustment tracks a trajectory rather than just hitting a target.

The obvious objection is that we don’t know the grammar yet. Even with precise control, how do you know what pattern to impose? Without decoding the full syntax of trajectories, rates, and contexts, attempts at control risk chaotic or null results. Vmem manipulation might be no more privileged than targeting downstream effectors like transcription factors.

This take is reasonable, but overstated. All the above mentioned results show us that partial grammars already enable targeted reprogramming. The researchers didn’t need a complete dictionary, they just needed enough vocabulary to run the experiment.

Iterative decoding is a tractable path forward. Machine learning on bioelectric datasets can identify patterns that predict outcomes like regeneration, enabling progress without full mechanistic understanding. You learn the language by speaking it, with feedback. Off-target risks diminish with closed-loop systems that monitor real-time Vmem response, potentially achieving specificity superior to genetic interventions where one gene affects many unrelated traits.

We don’t need to wait for complete understanding. We can work with control systems sophisticated enough to learn as they go.14

This is exactly what we’re building at AION.

Our thesis is that non-invasive bioelectric approaches applying electromagnetic fields and ultrasound can achieve the volume knob control that current tools lack.

We're starting with thymic regeneration post-chemotherapy, restoring immune function in cancer patients whose treatment has left collateral damage. The thymus compels us for two reasons: its central role in age-related immune decline, and the nature of the problem itself. These cells aren't destroyed but rather they've lost the signal to maintain function. Re-specify the target, and the tissue can find its way back.

The cells already know how to navigate. We just need to learn how to communicate with them.

Reaching me is easier—just send an email.

-Benjamin Anderson

Thank you Dr. Michael Levin, Justin Mares, @anabology and Kyrylo Kalashnikov for feedback on drafts of this post.

Chernet B. T., Levin M. Transmembrane voltage potential of somatic cells controls oncogene-mediated tumorigenesis at long-range. Oncotarget. 2014; 5: 3287-3306. Retrieved from https://www.oncotarget.com/article/1935/text/

Mahapatra, C., Gawad, J., Bonde, C., & Palkar, M. B. (2025). Bioelectric Membrane Potential and Breast Cancer: Advances in Neuroreceptor Pharmacology for Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. Receptors, 4(2), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/receptors4020009

Chernet, B., & Levin, M. (2013). Endogenous Voltage Potentials and the Microenvironment: Bioelectric Signals that Reveal, Induce and Normalize Cancer. Journal of clinical & experimental oncology, Suppl 1, S1-002. https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-9110.S1-002

Fraser, S. P., Ozerlat-Gunduz, I., Brackenbury, W. J., Fitzgerald, E. M., Campbell, T. M., Coombes, R. C., & Djamgoz, M. B. (2014). Regulation of voltage-gated sodium channel expression in cancer: hormones, growth factors and auto-regulation. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 369(1638), 20130105. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0105

Pio-Lopez, L., Hartl, B., & Levin, M. (2025). Aging as a Loss of Goal-Directedness: An Evolutionary Simulation and Analysis Unifying Regeneration with Anatomical Rejuvenation. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany), 12(46), e09872. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202509872

Clarence D. Cone, Jr.; Variation of the Transmembrane Potential Level as a Basic Mechanism of Mitosis Control. Oncology 1 June 1970; 24 (6): 438–470. https://doi.org/10.1159/000224545

The same researchers showed that the cell cycle could be reversibly blocked with a bioelectric switch and they were even able to induce mitosis in mature neurons by depolarizing them.

Cervera, J., Manzanares, J. A., Levin, M., & Mafe, S. (2024). Oscillatory phenomena in electrophysiological networks: The coupling between cell bioelectricity and transcription. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 180, 108964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108964

Vandenberg, L., Adams, D., & Levin, M. (2012). Normalized shape and location of perturbed craniofacial structures in the Xenopus tadpole reveal an innate ability to achieve correct morphology. Developmental Dynamics, 241(11), 863–878. https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.23883

Villalba-Galea C. A. (2017). Hysteresis in voltage-gated channels. Channels (Austin, Tex.), 11(2), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/19336950.2016.1243190

In neurons, this manifests as pinched hysteresis loops leading to memristor-like behavior where identical potentials produce different currents based on stimulation history.

As a friend and colleague Kyrylo Kalashnikov points out well here, although I obviously disagree re: privileging bioelectricity (:

Barring the counterexamples of cutting an arm off with a knife or giving someone a carcinogenic chemical. Thanks for the note anabology lol

Levin’s group has begun formalizing this. A 2019 paper showed that electrical potentials can function as “distributed controllers” of multicellular ensembles, with gap junctions acting as bioelectrical transistors. In 2025, this was extended into a complete “Regulatory Network Machine” framework, mapping the sequential logic embedded in bioelectric networks. Their key insight was that these systems are already sophisticated analog computers where the setpoint is an emergent property of the system’s dynamics as opposed to something stored in memory.

there is still so much to explore here...

Compelling case for treating Vmem as a coordinate system rather than just an on/off switch. The hysteresis point is underrated, same voltage landing different depending on trajectory feels like something most people miss when they think about bioelectric interventions. Building closed loop systems that learn the grammer iteratively instead of waiting for complete understanding is the righ approach imo.