Where the God is Buried

What Jung carved in stone for a friend who sold olive oil

In January 1927, Carl Jung lost his friend Hermann Sigg. Seven months earlier, he had dreamed of him. A death dream, though he didn’t recognize it yet.

In the dream, Jung and Sigg were driving together along Lake Geneva. As they drove, the landscape shifted. The lake became the Nile. Vevey became Luxor, built upon ancient Thebes, city of the dead where pharaohs were entombed in the Valley of the Kings. Switzerland had become Egypt. For Jung, Egypt was always the land of Osiris, the god who dies and is reassembled.

They arrived at a town square. Sigg said he needed something repaired on the car that would take an hour. They agreed to meet at the eastern exit of the town, specifically, the eastern gate, where the sun rises.

Jung walked through the dreamscape and eventually waited at the appointed place. Sigg never came.

When he finally found him, Sigg was angry:

“You can actually wait for me and do not need to run away from me.”

The dead making a demand on the living.

Wait for me. Do not run.

Sigg died on January 9th, 1927. He was fifty-two years old.

At his tower in Bollingen1, Jung painted a mural in his friend’s memory. He carved an inscription into the wall. A map of the process that had nearly destroyed him, compressed into thirty lines, occasioned by the death of a friend.

Here is what he wrote:

This is where the God is buried,

this is where he arose.

like the fire inside the mountains,

like the worm from the earth,

the God begins.

like that serpent from ashes,

like the Phoenix from flames,

the God arises

in a wondrous way.

like the rising sun,

like flame from the wood,

the God rises above.

like ailment in the body,

like the child in its mother’s womb,

the God is born.

He creates divine madness,

fateful errors,

sorrow and heartache.

like a tree

man stretches out his arms

and sees himself

as a heavenly man

that he did not know,

facing the world’s orb

and the four rivers of paradise.

And he will see the face

of the higher man and spirit,

of the greatest father

and the mother of God.

And in an inconceivable birth

the God frees himself

from man

from image,

from every form,

while he enters

the unimaginable and absolute

secret.

In memory of Hermann Sigg,

my very dear friend,

died on 9 January 1927.

This is what he carved for his friend who sold olive oil. Scholars of Jung’s Black Books call this “the culmination of the process of the rebirth of the divine that forms a central theme of Liber Novus.”2 Everything Jung discovered in his years of descent, the dialogues with Philemon, the shadow work, the slow construction of the Self, compressed into verse on a tower wall.

Read it again. Slower.

This is where. Here. In this stone. In this body. In this life.

The God was always present, buried. Like fire inside mountains, waiting for rupture. Like the child already formed in the womb before anyone speaks its name. The arising is excavation.

Notice what Jung includes in the process: He creates divine madness, fateful errors, sorrow and heartache.

Individuation creates suffering. The God is born through disturbance and sometimes the disruption of everything you thought you were, especially, through the death of the ego’s certainties.

“like ailment in the body.”

By 1927, Jung had spent over a decade in what he called his “confrontation with the unconscious.” Beginning in 1913, after his break with Freud, Jung deliberately induced visions and descended into them. He conversed with figures who emerged from the depths: Elijah and Salome, a figure he called Philemon who became a kind of inner teacher, and early forms of what he would later call the shadow and the anima. He transcribed these encounters in the Black Books, then elaborated them with paintings and calligraphy in what became the Red Book.

It nearly destroyed him. He later said he was “menaced by a psychosis” during this period.3 He also said it was the foundation of everything he subsequently built, the prima materia from which his entire psychology emerged.

The inscription is a survivor’s report. Yes, this is how it works. Yes, it feels like dying. Yes, it creates errors and madness. And yes, the God is born.

“Like a tree man stretches out his arms and sees himself as a heavenly man that he did not know.”

This is the moment of recognition.

The cosmic geography was always there. You just couldn't perceive it because you thought you were something smaller.

Then the ending, the strangest part.

And in an inconceivable birth the God frees himself from man, from image, from every form, while he enters the unimaginable and absolute secret.

The God is born in man, rises like fire, then creates madness and sorrow. Man recognizes himself as heavenly man and then the God frees himself from man, from image and from every form.

This is the movement of individuation that rarely gets discussed. The Self cannot be possessed or captured or made into an identity. It completes and departs into the "unimaginable and absolute secret."

Why did Jung write this for Hermann Sigg?

His obituary in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung called him “a very kind, very upright, farsighted businessman.” He was a friend and neighbor who invited Jung to North Africa in 1920 when Jung needed to escape the jealousies and politics of his professional circles.

The work doesn’t happen only in the consulting room. It happens in the space between two men driving into the desert, in the ordinary life of commerce and friendship, and in the death of someone you actually loved.

Sigg’s death preceded, by only days, one of the most important dreams of Jung’s life.

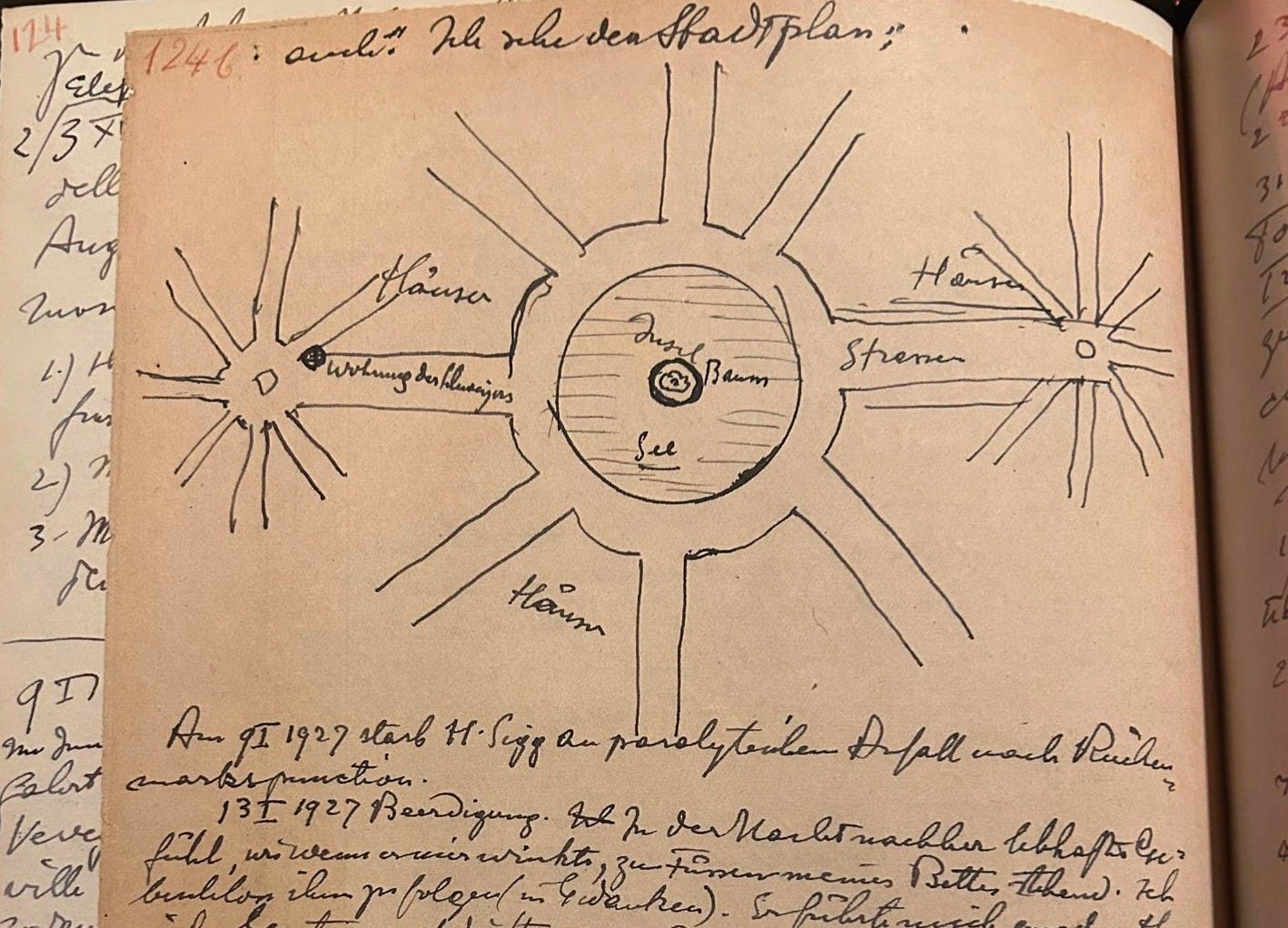

He called it the Liverpool dream. In it, Jung found himself in a dark, rainy city. Liverpool, which he later noted meant etymologically “pool of life.” The city was dirty and sooty, arranged in a pattern radiating from a central square. Jung and several Swiss companions, among them a certain Mr. Sigg, walked through the dark streets toward this center.

When they reached the square, they found a round pool with a small island at its center. On the island stood a single tree, a magnolia in full red bloom, glowing as though it were itself the source of light. The tree stood in eternal sunlight even as the city around it was shrouded in darkness and rain.

Jung’s companions did not see it. They talked about another Swiss who had settled in Liverpool, complained about the weather and wanted to leave. Only Jung perceived the tree.

He woke with a sense of closure. He later wrote:

This dream brought with it a sense of finality. I saw that here the goal had been revealed. One could not go beyond the center. The center is the goal, and everything is directed toward that center. Through this dream I understood that the self is the principle and archetype of orientation and meaning.4

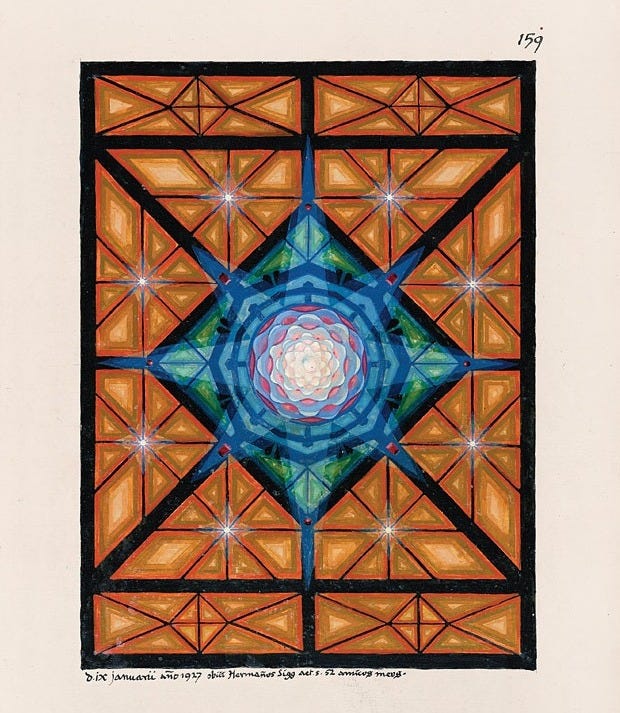

For years, Jung had been drawing mandalas, circular images that emerged spontaneously from his unconscious, without fully understanding what they meant or where the work was leading. The Liverpool dream ended his uncertainty. The mandala was the archetype of wholeness itself, the Self as the organizing center of psychic life toward which everything moves.

He painted that mandala in the Red Book with the inscription:

“9 January 1927 my friend Hermann Sigg died aged 52.”

The death dream seven months before, the Liverpool dream days after. Sigg present in both. Angry in the first, a silent companion in the second. Jung recorded this but never explained it.

Over his own grave, decades later, Jung had carved: Vocatus atque non vocatus, Deus aderit.

Called or not called, the God will be present.

The Sigg inscription tells you where to look.

Here, where the God is buried, where the God arose.

-Benjamin Anderson

Nostr: ben@buildtall.com

A primitive stone structure Jung had begun building in 1922 on the shore of Lake Zürich, a place without electricity or running water that he called “a concretization of the individuation process.” Pictures here.

Specifically, I assume: Sonu Shamdasani. This quote is in a footnote in Volume 7.

Footnote from Wiki: Storr, Anthony (1996). Feet of Clay: Saints, Sinners and Madmen, A Study of Gurus. Free Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-684-82818-9. Paul Stern made similar claims in his biography of Jung, C. G. Jung: The Haunted Prophet ISBN 978-0440547440

From Memories, Dreams, Reflections by C. G. Jung (p223)