Where the Pattern Breaks

Oppenheimer's forgotten lecture to American psychology

In 1955, the most famous scientist in America stood before the annual convention of the American Psychological Association in San Francisco.1 J. Robert Oppenheimer had built the atomic bomb. He had watched the Trinity test and thought of the Bhagavad Gita. At that very moment, his own government was publicly humiliating him for suspected communist sympathies.

He had come to talk about analogy.

Oppenheimer delivered a quiet demolition of the very model of science that psychology was desperately trying to imitate.

The Freight We Carry

Oppenheimer’s central claim was deceptively simple. Analogy is not a rhetorical flourish or a teaching aid but rather the fundamental mechanism by which human beings encounter anything new at all.

We cannot approach the unfamiliar except through the familiar. The old concepts are, as Oppenheimer put it, the “freight with which we operate.” This is the only equipment we possess. Science is therefore inherently and necessarily conservative. Not politically, but cognitively. Every new discovery begins as an analogy to something already understood.

The art is not in the analogy itself. It is in finding where the analogy breaks.

We can’t learn to be surprised at something unless we have a view of how it ought to be. And that is almost certainly an analogy. We can’t learn that we’ve made a mistake unless we can make a mistake, and our mistake almost always is in the form of an analogy to some other piece of experience.

Two Shadows, One Object

There’s a game I sometimes play when thinking through hard problems. Take two seemingly unrelated domains and sketch them as separate clusters on a page. Then start drawing lines. For each concept in one domain, look for a correspondent in the other. Where you find a match, draw the connection. The structure ports across.

The interesting part is what’s left over. The orphaned concepts with no line to the other side are where new ideas live. Either you’ve found a genuine difference between domains, or you’ve found something one field knows that the other hasn’t discovered yet. I call it the Pattern Spotting game.

Michael Edward Johnson at the Symmetry Institute has an alternative name for taking this seriously. He calls it “strong monism.” The weak version of monism simply claims that different domains of inquiry might be aspects of the same underlying reality. Two shadows cast by the same object. The strong version says we shouldn’t stop there. If two domains really are projections from the same underlying structure, they’ll have identical deep structure, and we can port theories from one projection to the other. His initial focus was phenomenology <=> physics. He continues:

I’d offer this as the meta-theorem of monism: every true theorem in physics will have a corresponding true theorem in phenomenology, and vice-versa. Literally speaking— if we go through a textbook on physics and list the theorems, ultimately we’ll be able to find a corresponding truth in phenomenology for every single one. I don’t know of any ‘strong dual-aspect monists’ out there doing this— but there should be.

This sounds abstract until you see someone actually do it. That’s exactly what Johnson did with his theory of Vasocomputation.

In Buddhist phenomenology, there’s a concept called tanha. It’s usually translated as “craving” or “thirst,” but practitioners describe it more precisely as a kind of micro-grabbing. When a pleasant sensation enters awareness, the mind reflexively tries to hold onto it and stabilize it. When something unpleasant arrives, the mind tries to push it away. This happens constantly, within 25 to 100 milliseconds of a sensation entering awareness. Buddhist consensus holds that this grabby reflex accounts for roughly 90% of moment-to-moment suffering.

Tanha is not yet a topic of study in affective neuroscience. Johnson thinks it should be.

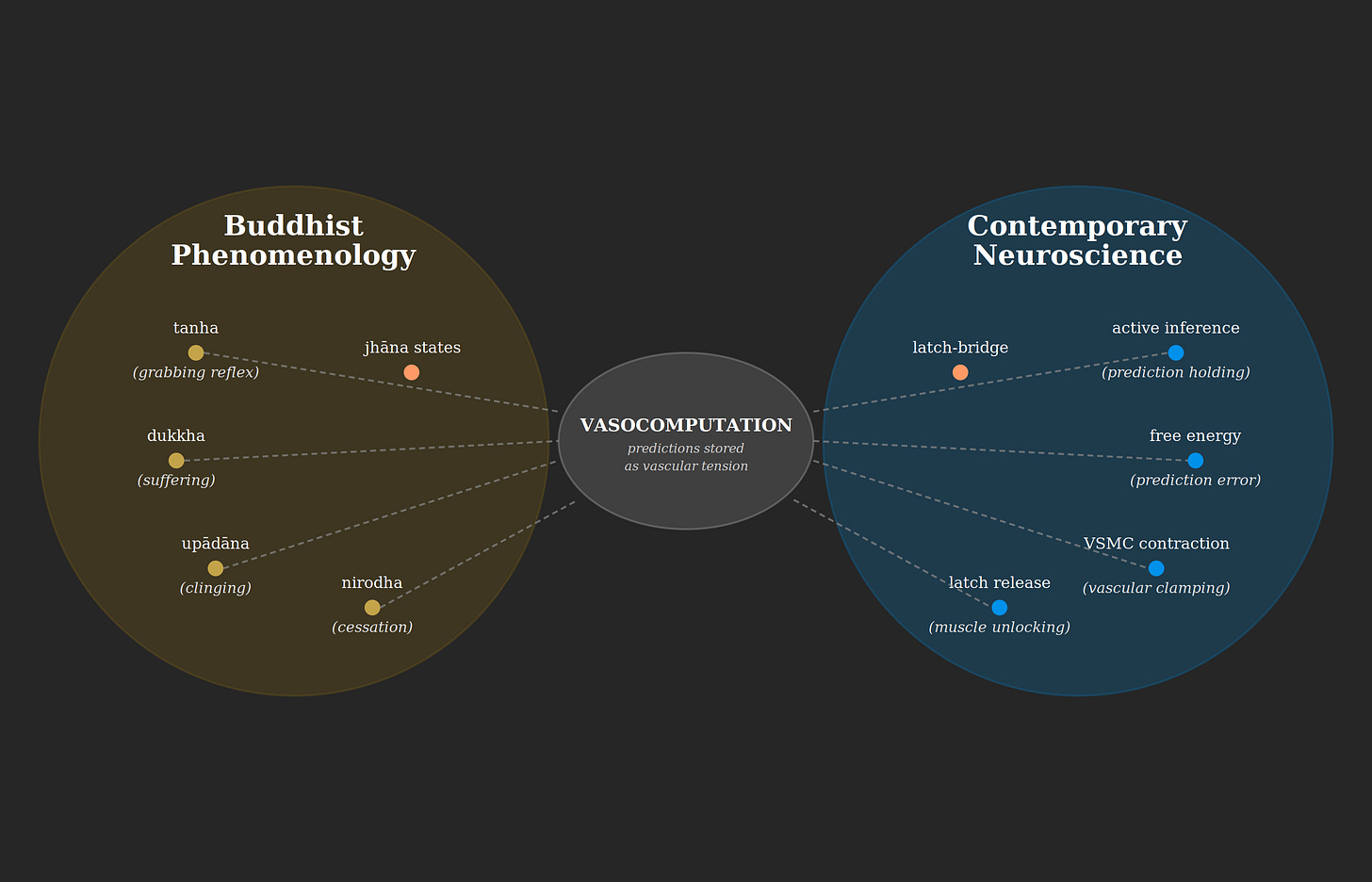

His approach was to take the diagram seriously with Buddhist phenomenology and its careful, millennia-old observations about the structure of suffering on one side and contemporary neuroscience, active inference, and the physiology of vascular smooth muscle cells on the other.

The overlap turned out to be striking. Active inference suggests that the brain impels itself to action by first creating a predicted sensation and then holding it until action makes the prediction true. Johnson noticed that this “holding” maps onto what Buddhists describe as the grabby quality of tanha. And both map onto something physical: vascular smooth muscle cells wrapped around blood vessels throughout the body, which can contract and “clamp” local neural patterns.

His hypothesis is that we store predictions as vascular tension. The smooth muscle contracts, freezing nearby neural activity into a specific configuration. If held long enough, the muscle engages a “latch-bridge” mechanism that locks the tension in place without requiring ongoing energy. This latched state corresponds to what active inference calls a “hyperprior” and what Buddhists might recognize as a deeply held pattern of craving or aversion that no longer updates.

What makes this interesting is not just the overlap but the gaps. Buddhist phenomenology has detailed observations about the timescale and phenomenal character of tanha that neuroscience hasn’t measured yet. Neuroscience has detailed knowledge of smooth muscle physiology that Buddhist practitioners don’t typically consider. Active inference has mathematical formalisms that neither tradition has fully exploited. Each domain has concepts that don’t immediately translate. And those gaps, if Johnson is right, are precisely where the new ideas will come from.

Back in 1955, Oppenheimer was describing something very close to this method. He illustrated it with five examples from atomic physics, each showing the same pattern of an analogy pushed to its limits, broken at a specific point and then finally rebuilt into something more powerful.

The concept of "wave" began with water, extended to sound, then to light with no medium, then to quantum mechanics where waves are unobservable probability amplitudes. The substance changed completely at each step but the structure of interference, superposition and diffraction persisted. The math transfers because the relations are the same.

When Newtonian mechanics failed at the atomic scale, physicists didn't abandon it. They demanded any replacement reduce to the original wherever the original worked. This is the correspondence principle. Every classical law survives into quantum mechanics with the one adjustment that momentum times position no longer equals position times momentum. That asymmetry is the entire revolution.

Radioactive nuclei emit electrons, but there are no electrons inside nuclei. Enrico Fermi proposed describing beta decay the same way physicists describe atoms emitting light. No one claims photons are “inside” atoms, yet light emerges. The analogy wasn’t perfect, but with fifteen years of refinement, it became a working theory.

The Japanese physicist Hideki Yukawa asked: if electromagnetic forces arise from photons, perhaps nuclear forces arise from a new kind of particle. He predicted mesons in 1935 from pure structural reasoning. They were discovered in 1947.

When new particles appeared that decayed inexplicably slowly, physicists recognized the pattern that slow decay usually means something is being conserved. They found the conserved quantity, though they couldn't name it better than "strangeness."

Each of the above cases reveals the same method of borrowing a structure, pushing it into unfamiliar territory, finding where it fails and then fixing it.

The danger, Oppenheimer warned, is taking the analogy too literally. He mentioned being nervous when he heard the word “field” used in both physics and psychology. The pseudo-Newtonians who tried to build sociology on mechanical principles produced “a laughable affair.” When physicists enter biology, their first ideas of how things work are “indescribably naive and mechanical.” This is what happens when you port the particulars rather than the structure

Johnson’s vasocomputation hypothesis could turn out to be wrong. What matters is that it’s the right kind of wrong. It makes specific predictions. It identifies specific points where the analogy might break. It gives us, as Oppenheimer said of Piaget’s work, “something of which to inquire whether it is right.”

In 1955, American psychology aspired to emulate physics amid internal debates over behaviorism’s dominance. The implicit message was that if you can’t measure it, it doesn’t count. If your sample size is small, you’re not doing science. Quantification was the mark of legitimacy.

Oppenheimer told his audience they were chasing a ghost. The deterministic, fully-objectifiable, purely quantitative Newtonian picture that psychologists were imitating had been abandoned by physics itself.

The atomic revolution had returned to physics exactly the concepts that the old mechanical worldview had expelled from respectable science.

Indeterminacy: predictions are statistical, and every event has in it “the nature of a surprise, of a miracle.”

Limits on objectification: you cannot describe a system without reference to how you’re observing it.

The inseparability of observer and observed: the electron has no position until your measurement creates one.

Wholeness: atomic phenomena are global and cannot be broken down into fine points without destroying them.

Individuality: every atomic event is unique, not interchangeable.

If a poor and limited science like physics could take all these away for three centuries and then give them back in ten years, we had better say that all ideas that occur in common sense are fair as starting points.

The concepts psychology thought it had to abandon in order to become scientific were being rehabilitated by physics at the exact moment psychology was abandoning them.

Just a Story

Then came what I consider the most subversive moment of the talk.

Oppenheimer had spent the previous year hosting Jean Piaget at the Institute for Advanced Study. Piaget’s method was clinical conversation. Extended dialogues with children, often his own, building elaborate structural theories of cognitive development from a handful of cases. By the standards of rigorous experimental psychology, this was almost embarrassingly anecdotal.

Oppenheimer praised it directly. Piaget’s statistics, he noted, “consist of one or two cases. He has just a story.” And yet Piaget had “added greatly to our understanding.”

He has given us something of which to inquire whether it is right.

This is the function of analogy at the generative stage. You don’t need certainty. You need structure in the form of a picture, a model or a story that organizes experience and tells you what to look for.

The Babylonians could predict eclipses without celestial mechanics. They observed when things happened and extracted patterns through what we might recognize as harmonic analysis. They got so good that their methods were still in use in India up until the last century, predicting eclipses within 30 minutes. Eventually, celestial mechanics gave us a structural understanding that could be extended, refined and corrected.

Piaget's developmental stages may not be exactly right, but they make phenomena visible. Before Piaget, you might watch a child insist that a tall thin glass holds more water than a short wide one, even after watching you pour from one to the other. You'd think the child was confused or not paying attention. Piaget provided the framework that the child hasn't yet developed conservation of quantity. Now the error is interesting. Now you can ask when and how that capacity develops. The story creates the possibility of surprise.

I make this plea not to treat too harshly those who tell you a story, having observed, without having established that they are sure that the story is the whole story and the true story.

The questions matter more than the answers at this stage. They’re what you get when you take the pattern spotting game seriously.

Near the end of his talk, Oppenheimer turned contemplative. If his picture of science was right, scientific life was going to be complicated. Many approaches, many languages and an enormous range from abstract thought to hands-on practice. There would need to be a lot of psychologists, just as there were getting to be a lot of physicists.

But amid all the collaboration, there remained something essential.

When we work alone trying to get something straight, it is right that we belong. And I think in the really decisive thought that advanced the science, loneliness is an essential part.

Piaget watching his daughter figure out object permanence is lonely work. It doesn’t generate publications with p-values. It doesn’t look impressive. But it might be where the actual insight happens.

Oppenheimer closed with a challenge: the texture of life, its momentary beauty and nobility, is worth paying some attention to.

The question is whether we’ll pay it, or keep chasing a physics that no longer exists.

-Benjamin Anderson

Nostr: ben@buildtall.com

View the complete talk on YouTube here:

love this!

This piece highlights something we’ve largely forgotten. Progress comes from compressing reality into provisional structures, not from mistaking measurement for understanding. Analogy is mechanism that lets new domains become thinkable before they’re formalizable. The failure mode is refusing to notice where the story breaks and what that break is trying to reveal.